The Meaning of a Cathedral

Note: This article was written by Dr. Glenn Sunshine and published here. It has been slightly edited and reformatted for clarity by John Hay, who added helpful illustrations.

When I got the news about the fire at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, I felt much the same way I did on 9/11. I lived for a time in Paris, and I have good memories of the cathedral. And besides, as a historian, I place a great deal of value on historical artefacts. As I watched the videos of the fire, it looked like it would destroy the 13th century windows and maybe the cathedral itself. When the first pictures of the aftermath of the fire came out, I was relieved that the damage was not worse and that so much of the artwork had been saved.

Almost immediately, people began looking for symbolic significance in the fire: it was emblematic of Europe’s rejection of its Christian heritage, or the survival of the gold cross on the high altar showed the victory of Christ over the fires of secularism. Others rejected the significance of the fire altogether, either from anti-Catholic sentiments or because the Church isn’t the building, it’s the people—a comment which misses the point altogether.

Rather than look for significance in the fire, I am here going to explain some of the significance of the cathedral, or more generally, of Gothic cathedrals. If understood properly, there is profound truth expressed in the building, a forgotten worldview anchored deeply in biblical imagery and in the idea that everything in the world has meaning.

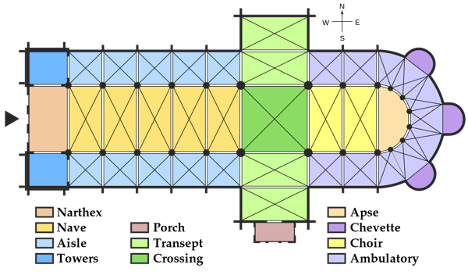

The Shape: Let’s start with some basics. The basic form of most Gothic Cathedrals is a basilica. This is essentially a long corridor (the nave) with an eastern rounded end called the apse, which contains the high altar. To the nave are added transepts that turn the overall shape of the basilica into a cross. Running along the edges of the nave are side aisles, which are separated from the nave by a row of columns. They have their own roof, well below the roof of the nave. The aisle around the apse is referred to as the ambulatory. Protruding from the ambulatory on the east end there may be rounded protrusions called chevettes, each containing small chapels.

The Orientation: The cathedral is oriented on an east-west axis. Since compasses were unknown in Europe in the Middle Ages, the line of the nave was established by the bishop holding up his crozier (i.e. his staff) when the sun rose on Easter morning; the shadow determined the orientation of the nave. The symbolism of this orientation was the critical point. To the medieval mind, Jerusalem was in the east. When Solomon dedicated the First Temple in Jerusalem, he prayed that God would hear the prayers his people offered toward that place (2 Chron. 6:19-40), and so people should pray toward Jerusalem. Thus, the cathedral was built with the apse to the east and with the main altar in the nave just east of the transepts. That way, most of the congregation, who would be in the nave, would be directing their prayers toward Jerusalem. Did they know the direction was not true east and that was not an exact bearing to Jerusalem? Of course. But the exact direction was not important; the meaning of the direction was.

The West Portal: On the west end of the cathedral was the main entrance. It was flanked by two towers, representing Boaz and Jachin, the two bronze towers at the entrance to Solomon’s Temple (1 Kings 7:15-22). In French Gothic cathedrals, the tympanum (i.e. the arch over a door) of the west central portal depicts either the scene in Revelation 4 of Christ in glory on His throne, or a scene of the Last Judgment.

This is significant for several reasons. First, the sun sets in the west, ending the day; this then becomes a picture of the end of time. As we enter from the west, we are not only heading toward Jerusalem (the east) but symbolically we are entering the heavenly sanctuary (the two towers connecting the cathedral to the Temple of Jerusalem, which was a shadow of what is in heaven (Heb. 8:5). But to enter heaven, we must pass under the Judgment Seat of Christ.

Color: This brings us to yet another level of meaning. Medieval cathedrals today have bare stone walls and statues. In the Middle Ages, the walls were whitewashed and the statues polychromed and gilded. Art restoration experts have examined the façade of the cathedral of Amiens in minute detail and have found microscopic traces of the original paint. They have thus been able to reconstruct what it looked like, and at certain times of the year Amiens will use lasers to project the original colors onto the cathedral at night to show it in its original glory. The statues are painted in bright, almost gaudy, colors. Although Amiens only projects colors on the statues on the West Façade, the interior statues as well as the piers, capitals, and columns were also brightly painted. The cathedral was thus bright and beautiful, far beyond anything most people in the Middle Ages ever encountered.

Light: But when you got into the interior, this was not yet the most important source of color. Light was very important to Gothic aesthetics. It had a wide range of significance: it was the first thing God created and represented knowledge, spiritual illumination, Jesus as the light of the world, and God Himself (1 John 1:5), among other things. Medieval church builders thus wanted to find a way to admit more light into cathedrals. They hit upon a combination of pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and flying buttresses which directed the weight of the roof away from the walls, enabling them to open the walls up for large stained-glass windows. These windows, which could be used for educating the faithful, filled the sanctuary with light and color. The blue windows shone particularly brightly on sunny days and the reds when it was cloudy. The windows were intended to remind the viewer of jewels—specifically, the jewels that formed the foundations of the New Jerusalem. So now rather than just praying toward the earthly Jerusalem in the cathedral, you were entering a model of the New Jerusalem when you passed under the Judgment Seat of Christ at the end of the day/the end of time.

The Sublime: And what a model it was! If you have never been in a Gothic cathedral, you cannot understand what the architects and artists were driving at. Pictures simply cannot do it justice. I have taken students to Notre Dame in Paris. When you went in, you were sent down the side aisles, which are beautiful and tall. Part of the way down was the entrance to the nave proper. The students were impressed with the beauty and height of the side aisle, but then I had them look up as they entered the nave itself. Their jaws dropped and their eyes got big as they took in the full grandeur of the cathedral. Gothic cathedrals are not merely beautiful; they are sublime—they simultaneously make you feel small and maybe even a little afraid while at the same time giving you a feeling of exhilaration much like you might feel in a tremendous thunderstorm or standing next to Niagara Falls. The soaring height of the nave in the cathedral directs our attention heavenward. The Cathedral is intended to be a picture and foretaste of heaven, lifting you above this mundane world and reminding you that the world is much bigger than what we see here. In the cathedral, heaven and earth, time and eternity intersect. It is the earthly extension of the heavenly sanctuary, the place where God and humanity meet. It is beautiful to reflect on the beauty of God, and it is sublime for the same reason.

All of this is the smallest sample of the meaning encoded in Gothic cathedrals. The design also includes numerology (if that bothers you, consider the importance of numbers in Scripture), sacred geometry, a decorative program designed to teach the faith to incredible levels of depth, and more.

The Medieval Worldview and Ours: Encoding all of these layers of meaning into the cathedral was only possible because of the medieval worldview. The medieval mind saw multiple levels of meaning in everything. The best-known example of this is medieval fourfold exegesis, which saw four layers of meaning in every biblical text, but similar principles applied even to mundane things like compass directions. Everything has meaning on multiple dimensions, and all of it integrates into a complex, multifaceted, but unified world.

This integrated vision of the world is one of the main things that separates the medieval mind from ours. And for all our modern science and all our knowledge, we come off worse by comparison. If it were possible to bring a medieval thinker to today, he would undoubtedly be impressed with how much we know and with our technology, but he would be bewildered by the fact that we only see the surface of things. We’re limited to the literal and factual. He would tell us that we know an enormous amount, but we understand nothing because we cannot perceive meaning in the bare facts around us. And that is why Notre Dame and the other Gothic cathedrals are so important. They shout to us that the world is charged with meaning and that all meaning is integrated in Christ. They call us to remember who we are and challenge us to take our destiny seriously. Like Psalm 8, they speak to us of how small we are yet how exalted we are in Christ. And they challenge us to see the world in the old, true way rather than in the sterile, one-dimensional way the modern world has foisted upon us.